No member of my “great cloud of witnesses” is more vexing to me than Alexander Solzhenitsyn, the Russian Orthodox writer who shows up at least twice or thrice every time I teach the history of the Cold War.

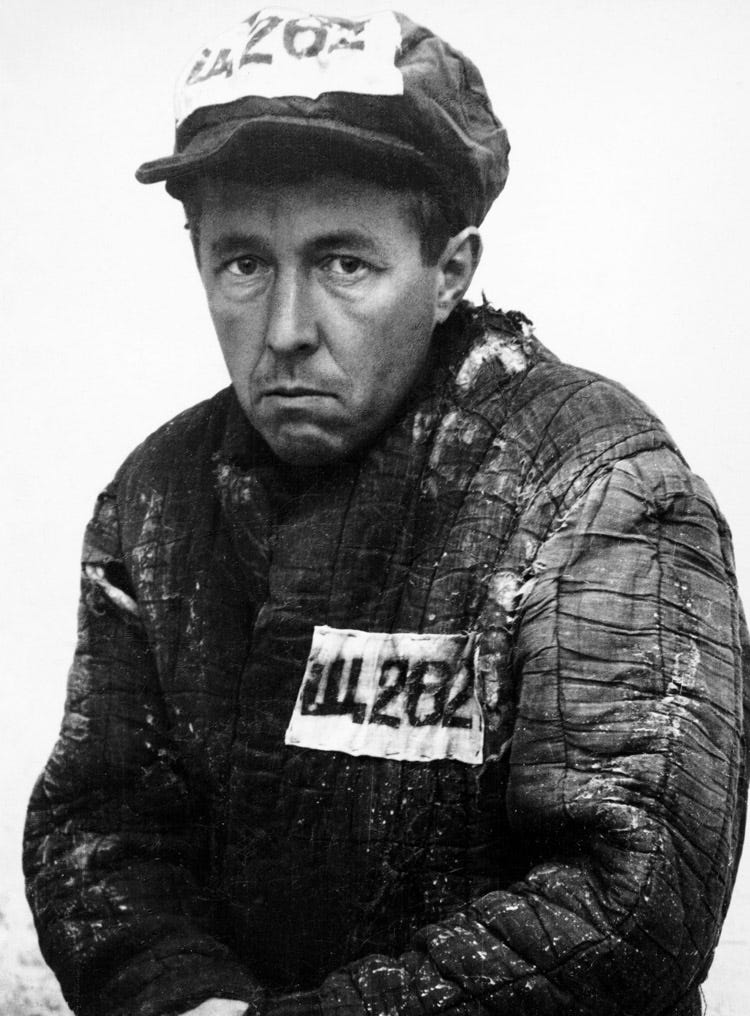

Despite being decorated for his courageous service as an artillery officer in World War II, Solzhenitsyn was arrested in 1945 for writing disparaging comments about Josef Stalin in a private letter. After spending eight years in the forced labor camps of the Gulag and three more years in internal exile, Solzhenitsyn was released after Nikita Khrushchev denounced Stalinism in a secret 1956 speech. He began to write about his experiences in the camp system, eventually publishing a semi-autobiographical novella, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, in 1962 — with the backing of Khrushchev.

With its spare prose and eye for detail, One Day offered Soviet and Western readers alike an intimate, unflinching look at the brutal system that belied the liberation and equality promised by Communist theory. (“You’re not behaving like Soviet people,” protests a former naval officer, when guards subject prisoners to yet another instance of capricious cruelty. “You’re not behaving like communists.”) Yet there were hints of humanity, as Solzhenitsyn also suggested how individual dignity and decency can survive even the harshest version of collectivization. Throughout the story, Ivan finds small ways to control (small) parts of his life, take pride in his work, and treat others humanely.

His day ends with a remarkable conversation that never fails to take my Bethel students aback. As Ivan prepares for bed, he chats with Alyosha, a Baptist who has been mostly silent throughout the story but now engages our protagonist in a conversation. “Your soul is begging to pray,” he tells Ivan. “Why don’t you give it its freedom?”

At this point, my students are excited to see a fellow Christian “share the gospel” (as one put it yesterday) in the midst of an officially atheistic society. But what this Russian Baptist means by “freedom” would surprise most Americans. Telling Ivan that he shouldn’t pray for a shorter sentence, Alyosha argues that their suffering, however unjust, is actually good for the soul:

Why do you want freedom? In freedom your last grain of faith will be choked with weeds. You should rejoice that you’re in prison. Here you have time to think about your soul. As the Apostle Paul wrote: ‘Why all these tears? Why are you trying to weaken my resolution? For my part I am ready not merely to be bound but even to die for the name of the Lord Jesus.’ [Acts 21:13]

It’s a theme that Solzhenitsyn would develop at greater length in the future. He was kicked out of the USSR’s writers union after Khrushchev’s fall from power in 1964 and endured growing KGB harassment. He continued to work secretively, publishing his multi-volume study of The Gulag Archipelago abroad in 1973. (It wasn’t released in the Soviet Union until the glasnost days of Mikhail Gorbachev.) In a section entitled “The Soul and the Barbed Wire,” Solzhenitsyn offers the Gulag as one of many examples from history of how “prison causes the profound rebirth of a human being.”

“Your soul,” he continues, “which was formerly dry, now ripens from suffering.” Harsh a school though it be, being the innocent victim of a totalitarian police state can teach Christians to love others — and to look more honestly at themselves:

Once upon a time you were sharply intolerant. You were constantly in a rush. And you were constantly short of time. And now you have time with interest. You are surfeited with it, with its months and years, behind you and ahead of you—and a beneficial calming fluid pours through your blood vessels—patience.

You are ascending….

Formerly you never forgave anyone. You judged people without mercy. And you praised people with equal lack of moderation. And now an understanding mildness has become the basis of your uncategorical judgments. You have come to realize your own weakness—and you can therefore understand the weakness of others. And be astonished at another’s strength. And wish to possess it yourself.

The stones rustle beneath our feet. We are ascending….

Finally exiled from the Soviet Union in 1974, Solzhenitsyn settled in the West — and was repulsed by what he took to be the corrosive effects of freedom. In a 1978 address to Harvard’s graduating class, Solzhenitsyn warned that while the West had secured individual rights denied in the East, plus greater independence from "state control,” it had also granted “destructive and irresponsible freedom… boundless space,” leaving modern life unable “to defend itself against the corrosion of evil.”

“Through deep suffering,” Solzhenitsyn continued, “people in our country have now achieved a spiritual development of such intensity that the Western system in its present state of spiritual exhaustion does not look attractive.” I doubt he’d find the America of the 2020s any more appealing than the one he knew in the last decades of the Cold War.

It would be easy to dismiss Solzhenitsyn, whose Russian nationalism eventually led him back to his homeland — and to some dismaying connections with Vladimir Putin. But he does speak for an ascetic strand of Christianity that embraces literal or metaphorical mortification as being good for the soul.

People who worship a savior who endured crucifixion and prepared his disciples to expect their own crosses should not be surprised that faith can grow in the rocky soil of suffering or adversity. After all, the freedoms we take for granted in the contemporary West are historical newcomers; most of church history is the story of people following Jesus in the midst of political and social systems we’d find unduly restrictive.

For that matter, there’s enough overlap between the lists of the world’s freest and most secular countries to make me understand where Solzhenitsyn is coming from. And followers of Jesus who live in contemporary America know all too well that freedom can be abused — though I wish we’d be as bothered by the dehumanizing effects of free market capitalism as we are offended by the unregulated expression of unpopular ideas or disturbing images.

Nevertheless, “post-liberalism” has become sufficiently popular among Western Christians of a theologically conservative bent that I think it’s worth pointing out some of the ways that Solzhenitsyn seems both to overstate the spiritual benefits of imprisonment and to understate the spiritual benefits of freedom.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pietist Schoolman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.