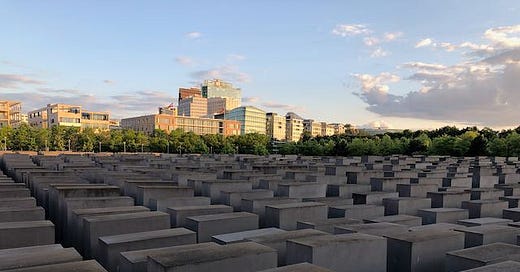

The Most Powerful Holocaust Memorial I've Seen

While German history has been a big part of my life and I’ve traveled to that country several times, I’d never been to its capital city. So when my colleague Sam Mulberry and I spent a week last month criss-crossing Germany, I made sure to end our tour with two days in Berlin. Our goal was to scout locations for a 2023 tour on the theme of “Christianity…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pietist Schoolman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.