For this morning’s final exam in Bethel’s Christianity and Western Culture class, students are writing one of their essays in response to this question: Where did you see yourself in our story?

In other words, we want students not simply to absorb and synthesize information about history, philosophy, and theology, but to think about the historical narrative and intellectual debates of the course as a mirror — one in which they should expect to see at least a partial reflection of themselves: the development of ideas or values that they have come to share, or a historical event whose effects have stretched into their own time, or the origins of a tradition or community with which they identify.1

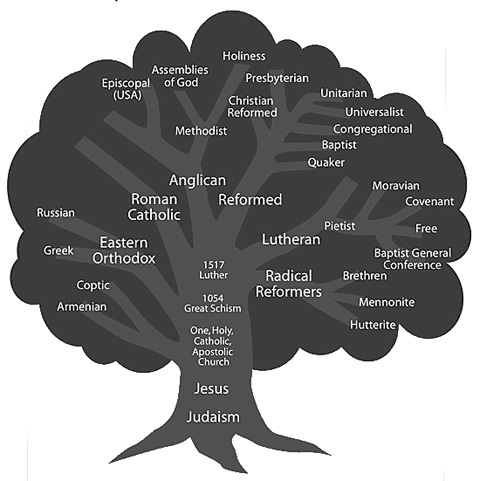

Particularly with that last type of answer in mind, we spent a lot of time near the end of the course starting to fill in a Christian family tree that kept sprouting new limbs and branches, as the Protestant Reformation and later events revived or initiated debates that caused Christians to cluster under different traditions: Orthodox, Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, Reformed, and Anabaptist, then offshoots like Puritanism, Presbyterianism, Methodism, and Evangelicalism.2

Because of Bethel’s particular heritage, I even got to spend half an hour on Tuesday reviewing the origins of Pietism in 17th century Germany — and its later impact on 19th century Sweden, some of whose many immigrants to America founded a tiny seminary that grew into our university. But as I talked students through writings from Philipp Jakob Spener and Johanna Eleonora Petersen, it occurred to me that we don’t do the same for the other half of Bethel’s heritage: the Baptist tradition.

After all, most of our students still come from churches that are either affiliated with a Baptist denomination like the one that sponsors Bethel, or with non-denominational churches that share key elements of Baptist theology that were absent from most of the CWC narrative. So for our last pre-class devotional reflection, yesterday I introduced students to John Leland, a Baptist minister in the early days of the United States who famously articulated a core Baptist principle: that authentic Christianity requires not only religious liberty, but the separation of church and state.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pietist Schoolman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.