Originally, I was going to title this last chapter something like “How Can I Use Technology Well in College?” I thought about addressing everything from taking online classes to using Google for research, and I was going to share survey feedback from students who shared hard-earned lessons about the distractions of social media and video games.

But while those are all relevant issues, this isn’t meant to be a comprehensive guide. And there’s one technology that’s currently attracting more attention than all others at the moment. In fact, I daresay that the single most pressing issue in higher education right now — whether you’re a student, professor, or college president — is something called generative artificial intelligence. Most famously, large language models that have been trained on enormous sets of (human-created) data to mimic humans.

So what does it mean for higher education that there are forms of AI that can seem to do things that, just a couple years ago, only humans could do? AI can even help answer the questions that I’ve raised in this book; chances are that you’ve actually encountered a bot of some sort during the admissions process. And you may soon interact with them serving as teaching assistants and writing tutors. But most importantly, you’ve probably already noticed that AI seems to do work that students used to have to do on their own: brainstorming ideas, finding and summarizing sources, writing everything from English essays to computer code, even making art and solving mathematical equations.

So it’s only natural to ask if — or how — you should use AI in college. I’ll get there, but first we need to ask some more basic questions.

First Things First

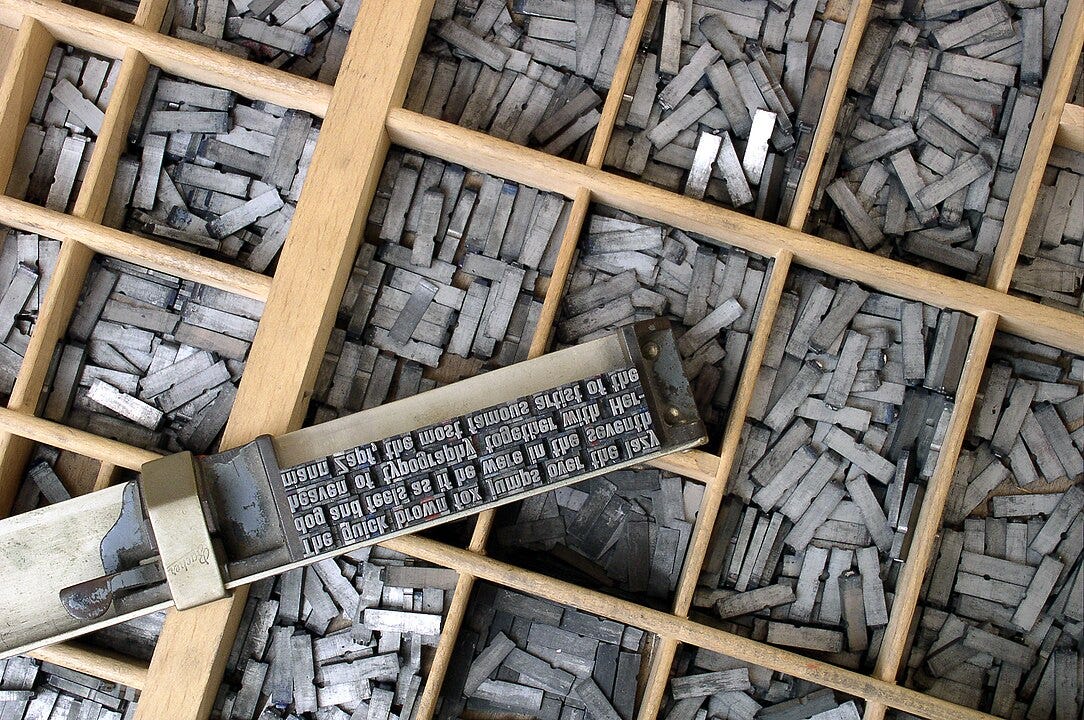

Even if there was no such thing as artificial intelligence, we’d still be using various forms of technology. Whenever the power goes out at work, I like to think that I can still teach my history classes without technology. But then I remember that the book is a technological innovation from Late Antiquity made much more affordable by the 15th century invention known as the printing press. Even the chalkboard where I scribble timelines and the pens and paper students still use to take notes are primitive technologies. Outside of the classroom, most of my work as a researcher and author — including the words you’re reading writing now — now depends on invisible networks connecting people near and far as they retrieve and produce information more effortlessly than humans ever have before.

So I try not to blame my students when they take technology for granted.

But I do want them to be discerning about their use of technology, especially if they’re fellow Christians who should beware the dehumanizing effects of machines, or at least be attentive to the ethical challenges they pose. That’s all the more true now that we’re rushing headlong into the age of AI: if anyone should be thinking carefully about the implications of artificial intelligence, it’s students and teachers called to develop the natural intelligence of human beings.

I think the starting point here is a simple principle: We never use technology just for the sake of using technology. It’s a means to something else, not an end in and of itself.

So before we ask about using AI at college, we should first review your reasons for going to college. Are you in college primarily for personal exploration or transformation, or to complete a transaction that will lead to a career? Can AI serve as a means to any of those ends?

My guess is that if you’re in college for either of the first two purposes, you won’t actually struggle too much with the use of technology in the Age of AI. If you could explore yourself and your world or transform your identity and ideas using AI, you wouldn’t need to go to college in the first place. But you already sense that those are innately human activities that machines can perhaps assist, but never replace. You don’t need me to tell you that a bot can’t form new relationships for you, can’t immerse you in other cultures, can’t let you try out new activities, and can’t ask or answer questions that refine what you believe and why you believe it.

Those of you with an exploratory or transformational mental model of college may feel social pressure to go along with how your peers use a tool like ChatGPT or QuillBot. But as long as you keep your ultimate purpose in mind, I don’t think you’ll ever confuse technological means for human ends.

So I’m primarily aiming this chapter at those of you who take the transactional view that college isn’t important for its own sake, but because it promises to equip and credential you for later work. For if you’re so focused on what comes after college that you don’t actually value what you learn in college itself, you’ll constantly be tempted to let technology not just assist your work, but give you a way out of it.

Is Using AI in College a Kind of Career Prep?

Now, if you’re in college primarily to prepare for your career, you might want to push back here. You could argue that it’s important to use technology as a college student so that you can practice doing the same thing the rest of your working life. My university’s most popular major, after all, requires its students to take a first-year course that does nothing but teach business applications like spreadsheets, word processors, and presentation software, tools those students will use in virtually any corporate job. Even in disciplines like mine, which don’t lead into any particular career path, you’ll get used to workplace expectations like completing tasks according to a deadline, communicating in a professional manner, and collaborating with members of a team on a shared project. And even studying ancient history can train you to use tools as contemporary as web searches and ArcGIS.

Nowadays, we hear a version of that argument from AI enthusiasts who want colleges to do more, not less, to integrate artificial intelligence into higher education. “The big picture is that it’s not going to slow down and it’s not going to go away, so we need to work quickly to ensure that the future workforce is prepared,” the head of the National Association of Colleges and Employers told Inside Higher Ed last year. “That’s what employers want. They want a prepared workforce, and they want to know that higher education is equipped to fill those needs of industry.” Teaching students how to use AI tools like Gemini or Grammarly is just the 21st century version of “the days when we shifted from classic office tools to more sophisticated ones toward the end of the 20th century,” argued online education advocate Ray Schroeder in the same publication. Yet not long ago, a couple of college students in North Carolina surveyed peers at several research universities and found that only 3% “felt very confident that their education would help them secure a job in a field involving AI.” They urged universities to create AI courses, workshops, clubs, and even certifications, to “further prepare students for success in finding employment and allow them to perform effectively when they land that post-graduation job.”

Even if college is a good place to practice integrating AI into your workflow, you’ll still need to beware pitfalls that I’ll get to in the last section of this chapter. But while we’re thinking about the relationship of college to career, let me give you two transactional arguments against embracing AI too quickly and too tightly.

We could start with bots’ tendency to invent false sources, and even to lie when caught doing so, since that’s bound to have negative effects for you at some point. But the bigger problem for transactionally-minded students is what happens to them when AI is actually effective in simulating the learning that humans are supposed to do in college. If you let AI do much, even most, of your work in college, you won’t actually acquire the knowledge and skills that you’ll need in the workplace.

For example, if you’re majoring in computer science and realize that this MIT professor is right “that AI can do more and more types of coding as well, or almost as well, as human beings,” you’ll be tempted to let such a tool do your work for you, especially in the introductory courses that give you a foundational understanding of programming. Not that it’s just a STEM problem. Let’s say you decide to major in political science or history — not because you’re curious about the past or interested in government, but simply because those are the two most common majors for law students. If you then let ChatGPT not only write your college papers for you, but do the reading and research for those assignments, you’ll never develop the very skills that you’ll hone in law school and use in the practice of law.

Or consider a more fundamental problem. The transactional view of college assumes that employers are waiting to hire college graduates to fill roles in their organizations. That’s generally true and will probably stay true in most fields, but if you’re an employer, one benefit of a technology that seems to think and communicate like a human is that it can replace the need to pay humans to do that work. If that MIT researcher is right that AI can code at least as well as proficient humans, how many new computer science and computer engineering grads will be hired for entry-level jobs? Indeed, those majors had two of the highest unemployment rates in the most recent jobs report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, more than twice the rate for their peers in theology and art history. The unemployment rate for marketing majors was similar to the overall average, but the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChapGPT) has predicted that “95% of what marketers use agencies, strategists, and creative professionals for today will easily, nearly instantly and at almost no cost be handled by the AI” in the coming years.

Not to say that you shouldn’t choose such majors! I have no doubt that humans will continue to be paid to develop apps and to prepare marketing campaigns. For that matter, humans will continue to do the truly creative and innovative work in any industry, since generative AI doesn’t actually generate anything new. But if you’re only picking a major because of its career prospects, first pay attention to how advances in technology are reshaping that field. Better yet, follow my earlier advice and pick a major because you love to study it — then actually study it, with technology as an assistant to you rather than a replacement for you.1 And whatever your major, don’t let a bot do your thinking and your writing in the liberal arts courses that almost every American college curriculum requires, since they’re there in part to develop the “soft skills” — and capacity for ongoing learning — that will be even more important as AI reshapes the workforce.

How AI Can Get in the Way of Your Vocation as a Student

As I write this chapter in July 2025, AI — and how colleges respond to it — is very much an emerging technology, changing by the month, week, and maybe day. So it’s hard to know what else to say that won’t soon be obsolete.

But I think I can offer one final word on this topic to new college students of any major, and especially to those who view their studies transactionally: make sure to heed what your college and your professors tell you is and isn’t acceptable about AI use.

It may be that you’ll go to a school or enter a program that emphasizes integrating AI. But even the most AI-happy college or major will impose some limits on how you’re supposed to use and not use that technology. You’re almost certain, for example, to find that it’s a violation of your college’s academic honesty policy to copy and paste something from ChatGPT — or, for that matter, from Wikipedia or another website — and then pass it off as if you wrote it yourself. Presenting the work of another human — or a human-like intelligence — as if it’s your own is the very definition of plagiarism.2

So whatever your personal views about AI, you’d best know those limits and adhere to them, for three reasons.

First, and most practically, while colleges fully expect that students learn through making mistakes, breaking rules does have consequences. When you enroll at a college, you accept its policies on the use of AI, other digital tools, and the networks they work through. When you take a course, you agree to the expectations and requirements that your professor lays out in her syllabus. Now, it’s harder for professors and deans to catch AI cheating than other kinds of academic dishonesty. But our tools for AI detection are evolving right along with AI itself. If you get caught, you risk your grade and — if it becomes habit — your continuing enrollment.

But even if you get away with plagiarism, you’ll still undermine your reason for being in college. First, as I’ve already argued above, you’ll be earning a diploma that opens the door to a career for which you’re not actually prepared. You may avoid an F for cheating, but your shortcomings will eventually be revealed, likely at the cost of your job and maybe your career. But worse yet, agreeing to abide by rules then quietly breaking them is fundamentally dishonest. Even if you don’t get caught violating that trust, you’ll still teach yourself to become a certain kind of person.

This is a kind of learning that Christians should be particularly attentive to in college. At a time in life when you start making choices large and small for yourself, you’re not just training your hands or filling your mind. You’re shaping your soul. Whether professors notice your behavior or not, whether you honor your commitments or break them will still form in you certain character traits — virtues or vices — that will be hard to unlearn later on. When AI offers a shortcut to the hard work of being a college student, the most important question you have to ask yourself isn’t whether to keep your word or cheat; it’s whether you want to become a truthful person or a deceitful one, a hard worker who seeks ongoing improvement or someone always looking for the easiest path forward.

Now, you may think that college rules limiting AI use are simply misbegotten, relics of an earlier age. As long as I cite ChatGPT as one of my sources, why would my professor ban its use altogether? Why can’t I let a bot write basic code in an introductory programming course, if that’s how the industry itself works? Why can’t I use QuillBot or Grammarly to make my writing sound academic for now, knowing that I won’t use that style or tone in my future job? Those aren’t unfair questions; I strongly encourage you to put them to your professors and discuss them with your friends.3 But at a certain point, you need to accept one more principle of higher education: college is fundamentally an exercise in trust.

Since the vast majority of your learning takes place outside of class, professors like me need to be able to trust that our students are doing what’s expected of them when we’re not watching. That’s why academic dishonesty is so corrosive, but also why I’ve come to accept that I shouldn’t try to catch all cases of AI-related plagiarism or other forms of cheating. I could try to investigate every instance, but that would just replace a relationship built on a trust with one built on suspicion.

But by the same token, I beg you to trust that your professors have good reasons for putting AI-related boundaries in place, just as your college has good reasons for requiring you to take that class in the first place. Those reasons may differ from your reasons for taking the course or completing the major, but that doesn’t make them pointless.

So let me close a chapter on cutting-edge technology by reiterating two timeless principles of education you’ve already encountered in earlier chapters. First, you’ll get more out of your education if you go into every class trusting that you have something to learn from it. Something that may not be predictable. Something that may be incredibly important to you, even though you don’t (yet) see how it fits into your goals for college and career. Something that you won’t learn if you let technology do the work for you.

But you’ll only learn that something if you do the actual work of learning. So second, remember that whatever your ultimate goals for college and its aftermath, your primary calling during those years is to be a student — to study yourself, your world and its people, and the God who created it all. As a college student, as in any other Christian vocation, “be steadfast, immovable, always excelling in the work of the Lord because you know that in the Lord your labor” — even educational labor whose point you don’t fully understand, labor that might seem easier to hand off to ChatGPT — “is not in vain” (1 Cor 15:58).

Next: “Last Words of College Advice.”

So I don’t sound like a total technophobe here… I just read a fascinating article by a civil engineer at Georgia Tech who teaches a course on “Art and Generative AI,” meant to help his future engineers not only use AI well as a tool but to recognize its “limitations and harness its failures to reclaim creative authorship.”

Where things get murkier is when you use AI for some steps in the writing process, but not others — e.g., to brainstorm ideas for paper topics early on, or to polish the mechanics and style of your rough draft before you submit the final version. I think you’ll find that different professors have different philosophies here, so make sure you read the syllabus closely — and ask questions if it’s not clear to you what’s allowed and what’s prohibited.

At this point, I address AI in my syllabus and then talk through that policy on the first day of class. In classes that are writing-intensive, we come back to it before the first essay or at some point during a research project.

Could artificial intelligence fool programs such as Turnitin? If Artificial Intelligence is used as a tool like an encyclopedia, or Wikipedia, maybe. I believe all compositions need to be original work, with citations, just like the era before Wikipedia and the Internet.