On Monday I wrote about a document calling itself a confession of “evangelical conviction,” and noted that some of its earliest signers were leaders of “institutional evangelicalism.”1 When I shared that document on social media, I described myself as “a Christian who continues to identify with the evangelical tradition,” an identity that’s only become clearer to me for having spent several years as part of a mainline Lutheran congregation.

But here’s the thing: according to a significant new historiographical article, neither that document nor yours truly necessarily fits the definition of evangelical.

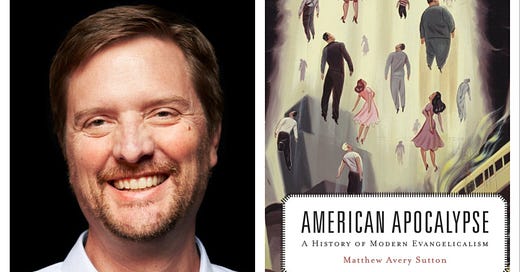

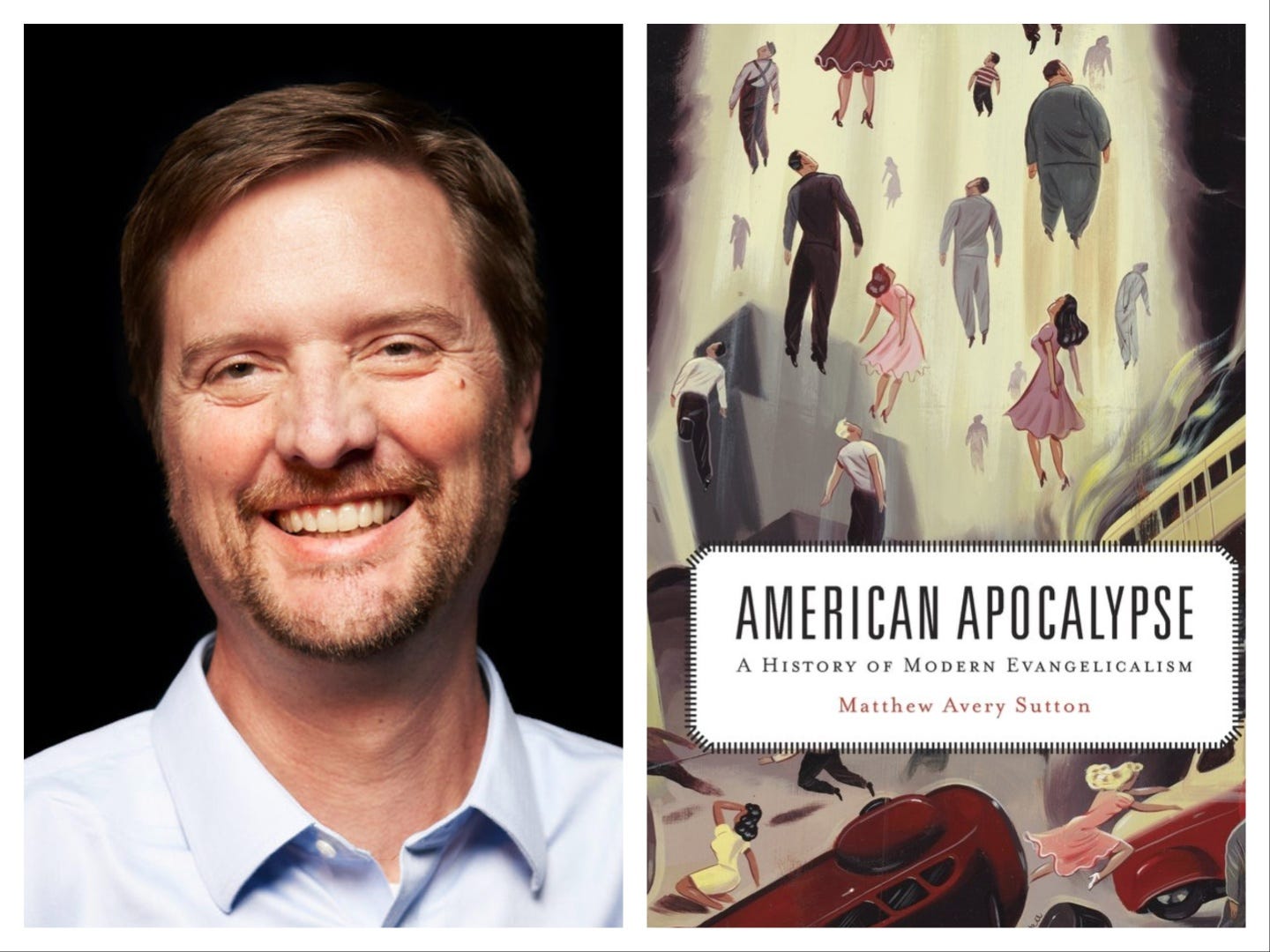

According to all sorts of American religious historians I follow, the newest issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion includes an article by Matthew Avery Sutton that either helps scholars use the term “evangelicalism” more accurately or completes misunderstands it, depending who you ask. Our library doesn’t yet have that issue, so I haven’t been able to read the full essay myself. But here’s how Ansley Quiros summarized Sutton’s “field-defining” set of arguments at The Anxious Bench, where she and Jake Rhett have been discussing the article in recent weeks:

In the 1980s, in response to the rise of the Religious Right, prominent religious historians occupying influential chairs and possessing access to institutional resources, cultivated a historical “consensus” that defined evangelicalism broadly, abstractly and optimistically, and created an unbroken lineage of both orthodoxy and orthopraxy throughout American history. However, Sutton argues, this imagined evangelical consensus, (which was subsequently adopted by many prominent secular historians largely ignorant about religion who “deferred to the experts”) was accomplished only by “decoupl[ing] the movement from politics, race, class, gender and sexuality.” A more accurate historical accounting reveals that there is, in fact, “no multi-century evangelical throughline.” Rather, Sutton writes, antebellum evangelicalism is a misnomer–“so elastic you could stretch it to eternity” while post World War II evangelicalism is best understood as a “religio-political coalition”: “a white, patriarchal nationalist religious movement made up of Christians who seek power to transform American culture through conservative-leaning politics and free-market economics.”

Variations on these arguments have been circulating for years now. When I taught a seminar on evangelicalism last fall, my students engaged with several of them. We started with a book on evangelical identity that was edited by three “consensus” scholars but included revisionist contributors who emphasized categories like politics, race, and gender more than theology or hermeneutics. One of them, Kristin Du Mez, went on to argue in our second book that “what it means to be an evangelical” — including what she found to be a generally patriarchal view of gender — “has always depended on the world beyond the faith.” Kristin and I joined The Anxious Bench in 2016, about the same time as Tim Gloege, whose studies of the economic bases of “corporate evangelicalism” made him question older, more theological definitions.

So I’m not unsympathetic to Sutton, whose 2015 history of evangelicalism (American Apocalypse) I recommended for student review in the fall seminar.2 But if he’s accurately describing what it means to be “evangelical” in recent religious history, then…

(A) There’s not much “evangelical” about the Confession of Evangelical Conviction, which explicitly rejects white nationalism and represents at least an implicit rebuke of Christian captivity to “conservative-leaning politics.”

(B) Moreover, if Sutton’s definition is correct, then I’m not much of an evangelical either.

Or as a Bethel colleague put it in an email last week: (quoted by permission)

…what do those of us whom Sutton's definition expels from the “evangelical” movement—that is, those of us who are integrationist in practice, non-patriarchal, non-nationalist, somewhat Anabaptist in our view of political power, slightly left of center politically, and critical of the corrosive effects of a free-market economy that has become largely unmoored from any non-financial restraints or ethical considerations—now call ourselves?

In a sense, my question reflects my impression that Sutton has done only half a job: he has redrawn the definition of “evangelical” but has made no attempt to “locate” those whom he has defined out of the movement.

Rhett raises a similar objection in part one of his conversation with Quiros. “Sutton rightly critiques the consensus historiography for smoothing over the rough spots of evangelical history and arbitrating ‘who counts,’ on the basis of a pre-approved list of criteria,” he concludes. “But in a way, he makes the same move by ousting those evangelicals who challenge the status quo. Sutton, too, is making judgments about who is a ‘true evangelical’” — in such way that Rhett worries that he’s leaving out evangelical feminists, Black Baptists, and Majority World theologians, among other “evangelicals on the margins engaged in ‘public and political efforts’ to redistribute power and resources in keeping with their religious convictions as evangelicals.”

To that, I’d just add a few thoughts of my own, some more considered than others.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Pietist Schoolman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.